As elaborated in the Philosophy section, magicians are dissuaded from sharing the mechanisms of tricks with ‘non-magicians’ – not least because doing so would spoil audiences’ experiences. And yet, exactly what can be shared with who are often grey matters.

For the most part, I am approaching the information about tricks in these web pages as a compact: you are being invited into the world of magic in the spirit of a student, like me. And study requires practice. In that spirit, I have asked readers to enact the steps set out for other Instructions.

In the case of the ‘Brainwave’ deck, though, this strategy comes apart for a couple of reasons that cut in somewhat different directions. One, you are unlikely to hthave a Brainwave deck to hand. Even if I encourage you, you may well not be inclined to purchase a deck simply to read this page (but please do). Should this stand in the way of my working through the details?

Two, as far as I can tell at this stage, trick decks seem to have an uneasy status in the world of magic: they are used by professionals from time to time but they are also marketed as novelty gimmicks for those without sleight of hand skills. Does this status mean that the mechanisms for Brainwave or other such decks can be more readily disclosed than sleights?

These are some of the questions I am grappling with while crafting this page. Tentatively I have presented relevant details below. However, for those unable to practice with a Brainwave deck in hand, an extra warning. You will miss much.

How can we assess our progress in learning? How can we more effectively develop skills? A common argument is that both are possible by deliberately altering practice. If, as contended by educationalists such as David Kolb, learning consists of mixing concrete experience with theorizing as well as abstract reflection with experimentation, then it is important not to get stuck in fixed practice routines that involve narrow kinds of learning.

This page recounts some of my experiences in using what was a new ‘device’ for me as of late 2018: namely, a so-called trick card deck. In my case, a gift of a ‘Brainwave’ deck provided an opportunity to expand on from ‘self-working’ and sleight of hand tricks.

Getting the Deck Out

Trick decks are typically designed to enable a specific effect. What kind of effort is entailed in using them then? Does their purposeful design mean ‘no skill is required’? The short answer to the latter question is: No, definitely not. The answer to the former will take a bit of time to develop...

To start at the start, when I was given the Brainwave deck, I did not know the intended effect or designed use. On inspecting the boxed deck, it is maybe not surprising then that I began speculating about what effect could be achieved and how. In this, my previous experience served as the basis for trying to fathom the Brainwave deck. Initially, the name conjured up a trick that would notionally be attributed to the mind reading powers of the magician, so something in the genre of ‘mentalism’.

To start at the start, when I was given the Brainwave deck, I did not know the intended effect or designed use. On inspecting the boxed deck, it is maybe not surprising then that I began speculating about what effect could be achieved and how. In this, my previous experience served as the basis for trying to fathom the Brainwave deck. Initially, the name conjured up a trick that would notionally be attributed to the mind reading powers of the magician, so something in the genre of ‘mentalism’.

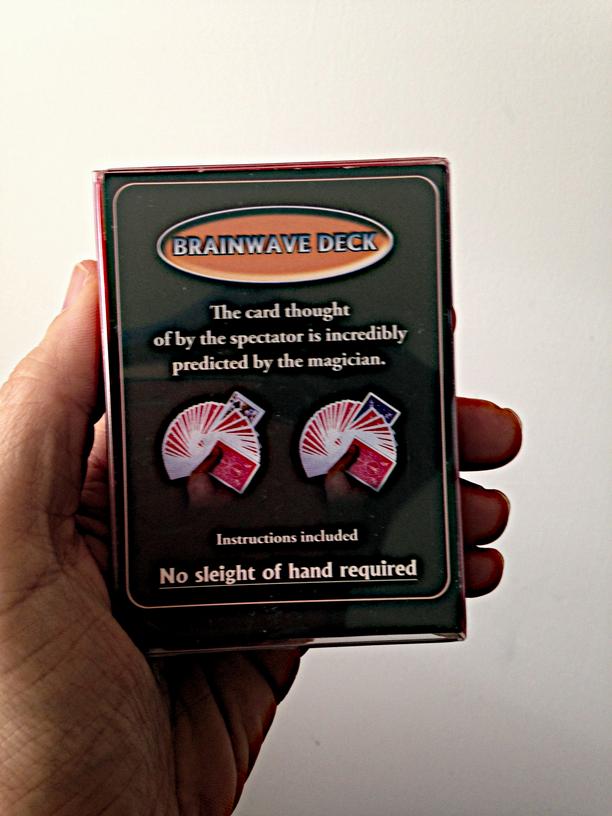

On inspecting the back cover of the packet box for clues (see photo), the images of the decks grabbed my attention. Interpreting them entailed first recognising the images were very similar and then noting there were differences within and between them too. As a way of discerning the effect and determining the mechanisms behind it, my focus moved back and forth between the two fanned decks in an effort to ‘spot the differences’ between them. What was noticeable was that the left-hand image has one card sticking outside the deck (QS) and the right-hand image appears as identical to the left hand one, save for what I assumed to be the QS turned faced down.

In short, in making the sense of the images I presumed a continuity in the cards and a temporal progression between the images moving from left to right. The former is interesting, because it is just that belief in continuity that many kinds of magic tricks play upon. Despite knowing this in the abstract, I did not question my continuity presumption when initially making sense of the Brainwave packet box. Instead, I wondered how the card sticking out was selected in order that it could be turned over to reveal its unique colouring. My initial thoughts about this selection was indebted to a type of sleight I had already learnt. Namely, I assumed that the card must be ‘forced’ by the magician; that is, the spectator would be compelled to select the card somehow.

From that understanding of the images, I then moved up to the text stating: “The card thought of by the spectator is incredibly predicted by the magician”. This confirmed my initial presumption that this effect was intended to be associated with ‘mind reading’. Catching the text at the bottom stating “No sleight of hand is required”, though, brought doubts about my presumption that forcing would be in play. I then circulated between the text and the images in order to assess how the card trick worked. I did not get much further in my thinking!

In making sense of the back of box packet then, I spent quite a bit of time seeking to determine the mechanisms at work. In contrast, I took the effect (the magician identifies a selected card) pretty much for granted. On the one hand, this is perhaps not surprising. The general effect sought in card magic tricks is often the same (card identification). On the other hand though, I think my preoccupations in this exercise speaks to many of the preoccupations in magic. Despite often downplaying the importance of the ‘secret’ mechanisms for tricks, as far as I have found in my limited experience to date, those interested in magic spend a lot of time discussing just that. While it might be widely argued that many skills and considerations are associated with ‘doing magic’, the puzzle of ‘how it was done’ tends to garner the bulk of attention. For instance, around the time of writing this entry, I read Jim Steinmeyer’s wonderfully rich book Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible and Learned to Disappear[1]. In relation to the points of this paragraph, he repeatedly notes the importance of a range of abilities needed in performing classical stage magic. And yet, certainly by my reading anyway, the secrets of ‘how they did it’ occupied centre stage in this history.

After opening the deck box, rather than turning to the written instructions, my first action was to place the cards in my hand. I then spread them out and mixed them around in order to get a feel for the deck. In doing so I immediately sensed that this deck was not like others…

Brainwave decks consist of blue and red colour backed cards stuck face-to-face against one another. As I would read in the instructions provided by its designer, Vincenzo Di Fatta:

The Deck

You are supplied with a full deck of 52 cards, of which half are red backed and half blue backed. If the deck you purchased is in a red case, the red backed cards will be the Hearts and Diamonds, and the blue backed ones, the Spades and Clubs. If your deck is in a blue case, the blue backed cards will be the Hearts and Diamonds, and the red backed ones, the Spades and Clubs.

In reading this opening paragraph, I did not try to comprehend its meaning in the abstract. Instead I worked the cards in my hands looking at them on both sides trying to assess the colour of the back side against the suit on the face side. This continued as I read the part of the instructions indicating:

The faces of all the cards have been treated in such a way that when two cards are face to face, they will tend to “stick” together as a pair. All the cards are assembled face to face in this way, and in numerical rotation as follows: Starting from one side of the deck with the Ace of Spades and continuing to the King, then the Ace of Clubs to the King. The Ace of Spades is paired with the King of Hearts, the two of Spades with the Queen of Hearts, and so on to the Ace of Clubs which is paired with the King of Diamonds, etc.

Trying to comprehend how the cards were ordered from this description was not easy and not something that I did simply by concentrating on the wording. In fact, I gave up on trying to get a definitive understanding from the text and instead attended to the deck in my hand. I spread through the cards and pried them apart to see which cards were stuck together in order that I could make my own sense of how they were aligned. I then read:

The deck should always be kept in this order. Place it in its case with the backs of the cards which match the colour of the case upwards, in this way the deck can later be removed from it without fumbling, proper side up to reveal the card named.

By this time, though, my working of the cards meant a number of the pairings were out of place. I then had to go through each pairing in the pack in an effort to place errant cards in the proper sequence. After that, I had read the part of the instructions indicating:

The named card will always appear face up in the face down deck, and it will have a different coloured back from the rest of the deck you seem to be using.

Not knowing how the trick was performed, I could not make much sense of why these details were being given.

Unsettled Witnessing

Getting not a little bored as a result of my flailing around, I sought out information beyond the written instructions. Those of us with ready Internet access have a considerable amount of resources at our fingertips. While written manuals provided a vital but fixed means of engaging with a wider community of practitioners in the past, today instructional engagement is also enabled through information and communication technologies.

Setting the cards to the side, I next conducted a web search for the Brainwave deck. As part of this, what came up included:

- Product Descriptions and Customer Reviews: As for any commercially available product these days, the top of my search list included sites selling Brainwave. Customers that (apparently) had purchased the deck offered commentary on its ease of use, production quality, etc. My personal favourite was by ‘K. Cross’: “Great trick, but because of the ‘code’ I can’t tell you any more than that”!

- Genre Classifications: I came to appreciate that the Brainwave deck was one of many trick decks placed under the heading ‘Rough and Smooth’.

This label refers to the roughing fluid applied to cards that causes them to stick together. From what I surmised, there is a whole sub-genre of ‘Rough and Smooth’ card magic with a supporting literature that dates back decades. - Promotional Materials: Exalting the ‘incredible feats’ one can perform with this deck, a host of text and video-based sites provide more or less information about the Brainwave deck’s effect and physical basis (as well as other card tricks also called Brainwave). Some include performance demonstrations, but without explanation of how the trick gets accomplished.

In addition, I found several instructional videos. As a couple of preliminary points of note, none of these videos contained anyone besides the performer. Also, none of the high end production web sites or YouTube channels of prominent magicians came up in my web search; an outcome I assume derives from the generally low status of trick decks.

Whereas making sense of the accompanying written instructions to my Brainwave deck required imagining what will be experienced, videos enable one to assume the position of an audience. A catch though is that witnessing is done through the situated seeing of someone whom knows what to look for. In this case given my prior reading of the instructions, I knew Brainwave decks consist of paired cards placed face-to-face in a specific sequence. That sequence means it is possible to determine the location of any card named. In putting the qualities to use, the video demonstrations displayed magicians spreading decks to the pairing where a named card was located, separating the paired cards, and then revealing that the named card was, in fact, facing up in a deck of cards otherwise all face down. Voila! As a second ‘kicker’, the performers all then turned the name card over revealing it has an alternative coloured back then the rest of the deck. Voila! Voila! How did the magician do it?

Watching demonstration videos, it seemed readily apparent to me that ‘each card’ in this deck was thicker than normal playing cards, but whether most or some audiences would likely notice this was not something I could easily determine, in part because of my foreknowledge.

As I got into watching the instructional videos for Brainwave, I picked up the deck again in order to replicate the demonstrated actions. That entailed taking the cards out, spreading them, and locating the place of the named card. Interestingly, while these steps were verbally elaborated in the videos I watched, none of them spoke in any detail to what I considered to be the ‘trickiest’ aspect: namely separating the paired cards sticking together in order to reveal the named cards as facing up. Most of my initial time practicing with Brainwave consisted of trying to find ways of ‘gracefully’ prying the cards apart and spreading the deck at different angles to hide the prying. Again, with my foreknowledge about the deck, for almost all the instructional videos I watched it certainly seemed the separation should be blatant to anyone viewing the video – I was not only person that appeared to struggle to get them apart! Even the scratchy sound the cards made when they got parted seemed clear. Again though I was not able to judge how easily audiences might detect these traces and decipher them as signals.

As with many of my other attempts to enact instructions, working through those for the Brainwave deck did not entail straightforwardly following the statements given. Aligning provides a perhaps more appropriate term to characterize what I was doing. Aligning here indicates how I sought to act in ways that I judged could best achieve the intended effect. Elements of the instructions were foregone or altered when I assessed they undermined the prospect for achieving the sought surprise.

In this case, for instance, one modification I made was in relation to enabling a rapid location of a named card in the deck. The instructions provided by Vincenzo Di Fatta suggested this be done by:

For easy location of the cards selected, and to save you from wasting time by counting, the sevens and Aces should be marked on their backs with a pencil dot. The 7th card down from the top should be dotted, indicating to you that it is a seven. The 14th card down should be marked in the same way to indicate the Ace of the next suit, and the 20th card also, to indicate the seven of that suit. Both sides of the deck should be marked in this way. These pencil dots will never be noticed by anyone not aware of their presence, but will help you enormously to get to the chosen card very quickly.

This was also echoed in all the instructional videos I watched, each advocated pencil dotting the 7th, 14th, and 20th cards. This is a technique for locating cards I previously become familiar with from Self-Working Card Tricks[2].

As was the case for that book, undertaking the instructions for the Brainwave deck repeatedly entailed using my own speculations about what I might see if I were an audience member to judge the appropriateness of the steps conducted, even while I could no longer see with the eyes of naïve audience members given my foreknowledge. In relation to the pencil dotting, I ventured audiences might well spot the dots — at least from time to time. That might be when the cards get spread. More likely though, if the audience member chooses a card that is paired with (or near) one of the 7th, 14th, and 20th cards, then the additional time spent showing a dotted card as part of revealing the named card would increase the likelihood of recognition. Instead of pencil dotting the 7th, 14th, and 20th blue and red cards, I used blue and red pens to fill in white circles in the design of the card backs.

Besides speaking to the difficultly of witnessing, I draw attention to the modifications of instructions to underscore how, again and again, magic as an activity is enacted with reference to onlookers — be they real, imagined, co-present, or virtual. While not unique to magic as an activity, this relationality is central to how sense is made of many instructions.

The Little Things…

In working through the written instructions and on-line resources, I was left with one overall impression: successfully using the Brainwave deck requires an awful lot of attention to an awful lot of issues. For instance:

-

Each card has a gritty feel on the face side. Therefore, should audiences physically hold the cards (say in wishing to inspect their named card), they might well detect something is amiss. As such, I judged it as important to find ways of dissuading audiences from handling the deck.

Notice anything?

Notice anything? - Since the cards need to be kept in their proper sequence and not separated, normal shuffling is not possible. More importantly perhaps, false shuffling used to assuage audiences’ beliefs about the cards being set up is also not feasible. As such, I judged that it is necessary to contrive circumstances wherein the deck can be pulled from its packet and used without the lack of shuffling being noteworthy.

- As the deck consists of paired cards struck together, its spreading requires a delicate touch. When the paired cards are pried apart, again, deftness is required in managing the spread deck to ensure other paired cards don’t become visibly unaligned or their double thick side edges get angled toward audiences. As such, I judged a significant amount of practice was required to undertake the requisite card control.

- Since the Brainwave deck comes in a packet (mine was a fairly standard looking red Bicycle one) that might not be the same colour as the card backs displayed to the audience (it depends on their choice), there is a danger that onlookers might wonder “Why are blue backed cards being taken out of a red packet?” (see photo). As such, I judged that would be necessary to cover or otherwise obscure the packet as much as possible.

In short, through the manner the material design of the deck implicates a whole host of considerations, Brainwave requires no small amount of effort to bring into play.

With effort come questions, which for me included: How could I use Brainwave alongside other tricks? What conditions are required such that it could be used without detection? Is all this effort worth the reward?

In terms of my performances, I started to use Brainwave at the end of my sleight of hand based session described in Going On – Part 2. As a way of minimizing some of the issues mentioned above, I used the deck only ‘after the end’. So after the announced end of the tricks, I put my standard card decks in a bag that included the Brainwave deck. Then, as part of the ongoing conversation, I found reason to show ‘one more trick’. I was then able to reach into the bag to pull out the Brainwave deck. Sequencing this trick after several others in which ‘the cards’ had been previously inspected by audiences was intended to both reduce the likelihood anyone would ask to touch the deck as well as marshal the previously established understanding that the cards were standard, ordinary, etc.

Through employing the cards in this way, I came to understand Brainwave as a trick deck in the manner it contrasted with other kinds of card magic. In terms of distinctions, many sleights are based on disguising control for haphazardness — for example, shuffling the deck can be used arrange, rather than randomize, cards. In the case of self-working tricks, dependence often gets mistaken for freedom — for example, an audience member might ‘pick any card’, but the underlying arrangement of the deck means that their choice can be readily fathomed. In the case of the Brainwave deck, at least as I have come to use it, extra-ordinariness gets disguised as ordinariness — the deck appears (and is made to appear) like standard ones.

Despite being able to achieve the sought effect without any detections (so far), I still have some concerns:

- While I have tried to cover the packet as fully as possible with my hand when bringing the cards out, I am still worried this is too much of a giveaway.

- Since the cards cannot be readily shuffled or otherwise worked for fear of them getting bent in such a way as the pairing don’t stick precisely together anymore, it is harder to break in the Brainwave deck compared to other ones. This, in turn, means that my deck has not yet gotten ‘scuffed up’ or ‘loosened’. The result is that the deck looks newer and feels crisper than the relatively broken in ones I use for performances. I could deliberately work the Brainwave deck, but I don’t know what impact this will have on the long term adherence of the cards.

- As long as l try to disguise my Brainwave deck as ordinary by using it alongside other decks, I am locked in using the standard red and blue Bicycle decks. I somehow think this kind of dependency could not have escaped the notice of the company…

After noting all of this, the question remains though, given the worked entailed, is the effort worth the reward? This is something I am still working through…

[1] Steinmeyer, J. (2004) Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible and Learned to Disappear. Da Capo Press, pp. 392. ISBN: 9780786712267.

[2] Fulves, K. (1976) Self-Working Cards Tricks. Dover publications, pp. 128. ISBN: 9780486233345.